10 years ago I wrote a post about fighting the decline in languages with an aim to giving practical strategies to build student competence, confidence and engagement. I thought I would revisit it 10 years later to see if older, wiser me had any better ideas.

Shortly after results day 2015 the Guardian ran a piece here reporting a continued decline in students taking GCSE languages. They also ran an analytical piece (largely crowd sourced from Twitter) investigating reasons for the decline. The table I used in the blogpost still remains true today:

| The Student View | |

|---|---|

| Reasons for | Reasons against |

| Enjoyable lessons | Oral exams |

| Useful skill | Memorisation |

| Good for CV/Uni | Fear of speaking in front of others |

| Mixture of exam and coursework | Not feeling competent enough |

| Cultural interest | Too hard and too much writing |

| Holiday use | “Never going to go there” |

| All-round skill improvement | Easier options around |

| Cognitive challenge | Everyone speaks English belief |

However, I would add a few extra things now that were maybe not so apparent to me in 2015. These include grading severity, which Ofqual researched and reported on in 2016. This continues to be an issues as reported on in 2023 and 2024 by FFT. Brexit and the rise of populism have definitely influenced student attitudes. They affect how students view the learning of languages and anything foreign. The loss of freedom of movement will likely have an effect too. Since 2015, we have had 2 new GCSEs and you can read some thoughts on the latest incarnation here. Yet still the decline continues…

Against such a strong tide, what can we do?

As in 2015, I suggest that the answers lie in our classroom. The Deputy Head in my school always emphasizes “focusing on the things we can control.” We may not be able to control the options blocks or options process that often impacts upon student take-up. We can control the lessons we deliver, the messaging we give and the climate we create around languages.

Building student capability

Probably the most important factor in taking GCSE MFL is the feeling of “I can do it”. As teachers, we know that GCSEs in MFL do not always score as highly as other subjects. To build this feeling of capability, there are three things we can encourage over key stage 3. Firstly, building a core knowledge and repertoire. Departments should have an idea of “by the end of key stage 3, we want them to know….” Admittedly, we need them to know a lot more but have you nailed down the top 100 items you really want to have cracked by the end of Year 9? What is the ground you are building KS4 on? How can you improve that? Lots of schools use sentence builders and again the advantage here is where the students can recall most things on the sentence builder. One teacher I worked with and learnt a lot from would use the same quizzes 3 or 4 times in a row before moving on. They wanted to be sure everyone knew what they needed to know. It wasn’t so much “do it until you get it right” as “do it until you cannot get it wrong.” Whilst familiarity may breed contempt and cries of “not this one again”, the pay off in terms of not being able to get it wrong and having phrases at your fingertips is worth it. At the risk of repeating my previous post, I’m going to stop here and move on.

Building student capacity

In a blog and book of the same name “High Challenge, Low Threat”, Mary Myatt writes “But what is crucial is that this is not a public, humiliating struggle which dehumanises the person, it is the private conversations we have with ourselves about what is working and what isn’t. The second strand to be considered here is that the circumstances are always low threat. No-one else can see our struggling to get the solution. No-one is pointing the finger. It is when we feel safe at this deep level that we are prepared to risk things and have a go.”

MFL is a high challenge subject. Speaking, listening and writing exams are high challenge. They are not low threat and we have to treat them as such but there are steps we can take to reduce the threat.

Building student confidence with speaking

I would suggest this one is the big giant that needs to fall in some students’ minds. Lots of students do not believe they are good at speaking. They are. I’ve heard them. But they don’t think that.

If I get the chance then while students are speaking in pairs, I might add little bits of feedback in books. A simple “2/3/26 Pronunciation great today!” is enough to build that feeling of confidence and competence. Or ” 3/3/26 all words great, just remember “hermano – h=silent” gives the student the idea that the overwhelming majority of what they said was fine and they just need to focus on one word. With the new GCSE valuing the ability to read aloud this focus on pronunciation will pay off in the long run.

Earlier today, I had a class debating cat or dog clothing as part of our clothes topic. Their opinions ranged from it’s cute to it’s embarrassing but they were delivered like they were reading the shipping forecast. I asked the class to do it again with “más pasión” and they duly obliged. The instant effect was that many sounded more confident. They said the same sentences but said them much better.

Really reward it. I have a system for rewarding speaking that I will one day share on this blog.

Until then, use your school reward systems to build the frequency with which pupils speak in your lessons. You can walk around with a clipboard, mini-whiteboard or notebook and just write down names of people who are speaking well and reward their efforts. After an activity, you can tell the students who you are awarding positive points to. Guaranteed in the next speaking activity, people will be going for it because it might be them you write down next.

Building student enjoyment:

The article above and student voice often references that language lessons are enjoyable in a different way to other subjects. Some subjects are enjoyable as they satisfy intellectual curiosity or there is tangible product resulting from the learning process. In MFL, we can build enjoyment in a number of ways.

Games / Activities

<<There was meant to be a picture here of students playing no snakes no ladders but the WordPress AI image generator had the creepiest game of snakes and ladders you have ever seen. Let’s just say the snakes on the game board were 3D and there were no ladders. Attempts to refine the image were unsuccessful>>

Students should enjoy our lessons. I believe there are a number of ways to increase enjoyment in lessons. Regular readers of this blog will know my fondness for purposeful games and these can be a great way to increase the enjoyment level of lessons but not at the expense of learning and reinforcing content. There are another 30 in this superb blog by Silvia Bastow. Beth Muten mentions a number in her blog here. This list from Steve Smith was very helpful in my early days as an MFL teacher.

Real life or close to – certain authentic materials

In my early days as a teacher, I remember attending training where we were told that authentic texts really motivate students. My experience of teaching MFL since is somewhat different. Certain authentic texts can really motivate students but they normally are too much for less able learners. That being said, some can work at all levels. At Key stage 3, I have used authentic menus as part of students preparing a drama where they order foods in a restaurant. Authentic maps can work well for getting students to practise directions. “Write directions from Camp Nou to the beach” worked on some maps from Barcelona. In both situations, I think the appeal for students comes from the fact that they are both life skills: How do I order food? How do I get from A to B? Other “real life” lessons that can done include ordering ice-creams, getting something you need at the chemist, arriving at a hotel/hostel or complaining about problems with your room. All four happened on my last school trip abroad so if any student asks “why are we doing this?” then i have a ready response.

Real life or close to – semi-authentic situations.

In a previous school, we would set aside a few lessons for students to script a restaurant scene based on Mira 2 or Expo 2 (if memory serves). A number of lessons would go into teaching the vocabulary, which included complaints. Students were then divided into groups of 4 and would script a restaurant scene. You need to be crafty with the requirements here. Starters, mains, desserts and drinks were a minimum. Complaints were expected from all bar one group member but that group member would pay the bill. This ensure everyone spoke sufficiently. Everyone wrote their lines, cues and the waiter’s line (example below).

Waiter: What would you like to order?

1

2

Me: I would like a…

In the days where peer-assessment was in vogue, students were asked to rate the dramas they watched out of 5 for fluency, communication, confidence and pronunciation. Did it flow? Did the people appear to communicate well? Did they sound confident? (even if not feeling it) and did they pronounce the words as they should?

The same idea works for arriving at a hotel, ordering ice-creams, chemist and a doctor’s surgery. For the latter ones you just have the people in line instead of round a table.

Without taking the kids abroad, roleplay scenarios such as these are probably the closest the kids have to practising a real life scenario they might encounter. These also tick the boxes of “holiday use” and “useful skill” in our table above.

Curiosity

MFL rarely gives the same amount of problem solving opportunities as other subjects. A favourite of mine is this lesson from TES where a murder has been committed and all of them ate the same thing. If you want to improve your food unit then it easily translates into other languages. Narrow reading also offers a way to engage the natural desire in us to solve a problem and find out. Giving pupils four very similar reading texts and the mission to “find someone who” can be motivating. Similarly, Dylan Vinales’ Algo Game has students trying to work out what the other person has and Gianfranco Conti’s Oral Ping Pong or mindreader have an element of discovery and trying to work out something.

Escape Rooms

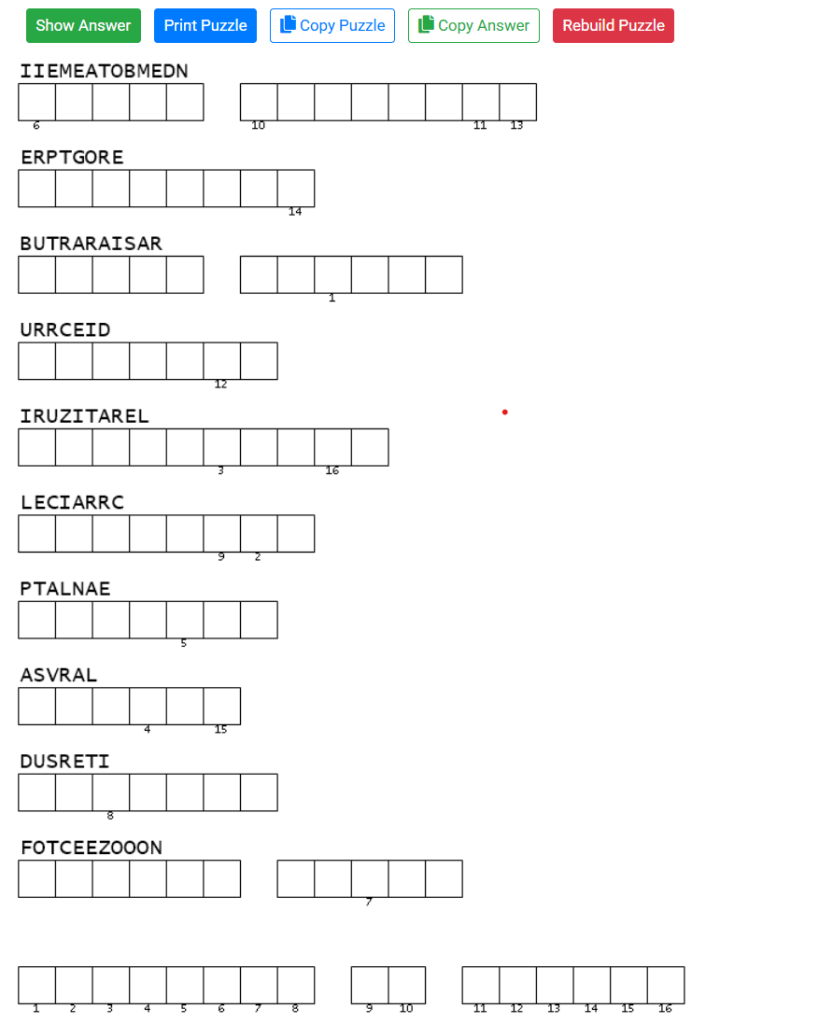

Lastly, escape room tasks also play into this desire to solve and they are readily buildable with apps such as Genially. A simple framework for a basic escape room is below. You can use some AI and Discovery Education’s Puzzlemaker to do the heavy lifting but be really specific with your prompts.

The example below uses the topic of the environment because it’s not the easiest one to make interesting (although I did try: here)

Task 1: Give a set of words and students have to find synonyms for those words. The first letter of the second set of synonyms should spell out a word.

e.g. desechos (waste) – basura (rubbish)

Task 2: Write a paragraph into a cryptogram puzzle. Hide a sentence in the puzzle with a missing word – the word from task 1.

Task 3: Put a load of vocabulary into a double puzzle. Hide a sentence in the puzzle with a missing word – the word from task 4.

Task 4: Give the students a series of 4 sentences where the first letter of each sentence is a letter that makes a word:

Proteger el planeta es responsabilidad de todas las personas.

Separar la basura facilita el reciclaje y reduce los residuos.

Ahorrar energía y agua ayuda a cuidar el medio ambiente.

Tirar menos plástico es fundamental para proteger los océanos.

Cuidar la naturaleza hoy asegura un mejor futuro mañana.

La contaminación afecta a los animales, las plantas y a los seres humanos.

Optar por productos reutilizables disminuye la contaminación.

Invertir en energías renovables reduce el daño ambiental.

The first letter of each line ultimately spells out “plastico”.

Task 5: Students give you the two complete sentences.

Competition

Competition is a good motivator, however it is easy to assume this engages boys. In the book, “Boys don’t try”, the authors are at pains to point out that not all boys enjoy competition. Sometimes this can be really effective with lower ability groups (see number 6 here for something that works well with lower sets). Competition needs to be a matter of the teacher’s professional judgment. Will it have an impact with this class?

Final Thoughts

Hopefully, something in the blog above has given you an idea or sparked off the memory of something you used to do and want to revisit. Ultimately, it is your classroom. You set the weather. Whatever those students think of learning languages, you have an hour or two a week to give them a lesson that is preparing them for when they venture beyond our borders. We cannot shift parental attitudes overnight, reverse national decisions to sever ties or engineer our options blocks so that 80% of a year group pick MFL (alas). We can however win the battle for hearts, minds and option numbers the way we always have: one student at a time.

Always loved this quote from anthropologist Margaret Mead (and President Bartlett from the West Wing).

I bet a good few of those thoughtful committed world changers needed to speak other languages to do it.